For all the twists and turns of the last 30 years, the brilliant songs and the invigorating reinventions, there are a few things you’ve always got to hand Tom Waits. The man’s a storyteller like no one else, and the more you look below the surface of his work, the more likely you are to find a host of narratives, sentiments, musical forms, and interwoven story arcs just begging for further attention.

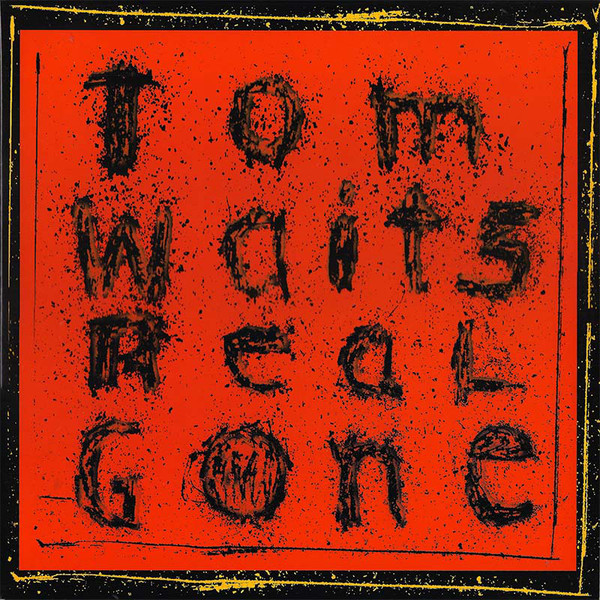

To anyone who’s spent more than few sleepless nights listening to Waits, it’s no wonder he’s so widely regarded as a kind of national treasure. Real Gone — the fourth full-length Waits has released since signing with Anti-/Epitaph in the late 1990s — only adds to the man’s sizable legend, a collection that at once revisits the musical tropes of Waits’ recent past while shooting off in some bold, new directions.

The 16 eclectic tracks on Real Gone each offer ammunition for more than a few hypotheses about where the new record fits into the storied Waits canon. Turntable scratches (courtesy of Waits’ son Casey) and looped vocal samples figure prominently into many of the record’s tracks, lending the record a slightly more contemporary edge than 1999’s bluesy Mule Variations or the atmospheric music-portraits of Alice and Blood Money, both from 2002.

Also figuring large on the record is guitarist Marc Ribot, whose spirited and jazz-flecked performances call to mind his collaborations with Waits on mid-1980s masterpieces like Rain Dogs and Frank’s Wild Years. (Also returning are longtime collaborator Larry Taylor and Primus alums Les Claypool and Brain, all of whom shine.)

While the record’s stylistic range challenges any sort of umbrella statement about recording techniques, many of Real Gone’s most impassioned tracks feel like they were captured live, on the fly, and in darkened, sometimes shadow-stained corners, something that will no doubt remind many of Bone Machine. Waits provides the evidence for each of these arguments. But the beautiful thing is that they really don’t seem to matter. Real Gone is incredible because of its songs, some of which stand among Waits’ finest work.

Listen and you’ll agree. There’s soul-fueled stomps (“Baby Gonna Leave Me,” “Metropolitan Glide”) and grimy rockers (“Shake It”). There’s bizarre, surrealist dance tracks (“Top of the Hill”) and subdued interludes that dance between jazzy verses and folksy reprises (“Dead and Lovely,” “Trampled Rose”). There’s Black Rider-style spoken-word monologues (“Circus”), sound experiments (the closing “Clang Boom”), and mournful ballads, some complete with a subtle backing track of softly mumbling angels (“How’s it Gonna End”). And then there’s the stuff that borders on the brilliant — the work-song hollers and call-and-respond refrains of “Don’t Go into That Barn,” the lurching sadness of “Green Grass,” the determined march and Waits’ ballsy, howling delivery on “Make it Rain.”

Only two songs in, though, Wait delivers the goods, the Caribbean/Latin-influenced barn-burner “Hoist That Rag.” Not since the heartbreaking funeral dirge “Dirt in the Ground” (from Bone Machine) have I found myself so consumed and captivated by a single song alone from a Waits disc. The song is the definition of intoxicating — the way its rhythm slips under your skin, the way its lyrics resonate, the way Ribot’s angular guitar solo knocks you off your feet and kicks the wind right out of you, the way the performance seems more captured than recorded, as if you were privy to some magical moment of musical communication that only Waits and his collaborators shared.

Waits also outdoes himself with the acoustic ballad “Day After Tomorrow,” an anti-war song in the much-fabled folk tradition. The difference between Waits and some angry, coffeehouse troubadour, though, is that Waits has the good sense to let the images and stories speak for themselves. Rather than attacking the listener with big messages or dollar-store jingoism, he does what he does best, illuminating the human element of things by giving voice to a weary soldier who yearns to return to the inviting simple, commonplace comforts of home.

(The sounds and smells of war and conflict also rear their head in “Hoist That Rag,” where Waits sings: “Well we stick our fingers in the ground / Heave and turn the world around / Smoke is blacking out the sun / At night I pray and clean my gun / The cracked bell rings as the ghost bird sings / And the gods go begging here / So just open fire when you hit the shore / All is fair in love and war/ Hoist that rag.”)

My first Tom Waits record was Nighthawks at the Diner, and, like many, I’ve relished the opportunity to grow with him and hear his stories change over the years. Real Gone may be just another chapter in the Waits story, but it’s an incredible one, one worth exploring if you’re new to his work or if you consider him, in some bizarre way, an old friend.

Find it, listen to it, discover it. This is the record of the goddamned year. – Delusions of Adequacy, Dec. 3, 2004