Much conversation on Brian Eno’s greatness ends up circling back to Music For Airports. Originally released in March 1978, the album might have the distinction of being the first record to self-identify under the genome “Ambient.” (The full title was, indeed, Ambient 1: Music For Airports.) And it is rightfully a landmark, with Eno masterfully working pre-constructed mechanical delays and tape loops to construct textures and ultimately narratives and listener-projected meaning out of a flutter of piano keys or a choral voice. It would be reductive to say the “non-musician” in Eno (his words) boils down just to Music for Airports. But even now, as we are greeted with another Eno set – this one his first collection of works created specifically for film – it is through the lens of Music for Airports that we can best understand what makes Eno’s work continuously relevant and wonderful.

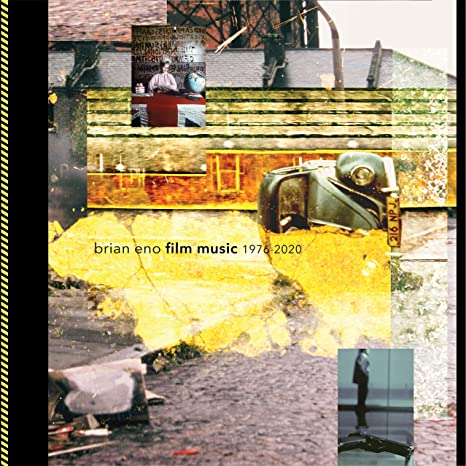

The new 17-track outing, titled, dryly, Film Music 1976-2020, starts in inspiring territory with the theme for Top Boy, where electronically manipulated marimba and what could be kettle bell keep an odd syncopation in front of a wall of synthetic color and, buried even deeper, choral voices. The song is slight, running just two and a half minutes, but it is a declaration of the tone of the record: ambient, yes, but not of the accidental or overly contextualized sort. Eno is painting with these selections, creating multiple narratives but also a kind of singular ambient work in its own right – one, perhaps, that represents the scope of his experience and feeling on the subject of scored film.

What you walk away from the LP hearing is highly and very intentionally subjective, as listener reactions to some of the best ambient works are. Some might be drawn to the noirish “Blood Red,” from a piece on Francis Bacon, others to the more structured, vaguely Talk Talk soul-balladry of “You Don’t Miss Your Water,” a William Bell cover borrowed from the Jonathan Demme comedy Married to the Mob. There are airy synth pieces (the oft-deployed “Deep Blue Day,” here quoted from Trainspotting) and dramatic, night-owl scene-setters (the appropriately titled “Late Evening in Jersey,” from Heat). But the areas where Eno really sticks the landing on the details are tough to shake. There, you have a gem like “Undersea Steps,” whose nail-on-the-head reverbed synths are accented by, yes, hints of sonar, or “Reasonable Question,” whose underlying groove and menace hints at a later, greater Bowie/Eno work like Outside.

There are, of course, the essentials, too, like “Final Sunset,” which was the only song Eno scored for an actual film on his conceptual Music for Films LP – also released, like Airports, in 1978. While that track’s whistling synth leads show its age a bit, it still sounds oddly relevant, engaging and of the moment, just as much so as “An Ending (Ascent),” which has been used in so many places it’s a wonder why it’s not scoring this review.

Ultimately, though, the record’s best moments again circle back to the hypnotism and cycling tides of Music for Airports. In this, it’s hard to ignore “Design As Reduction” from RAMS, whose original soundtrack album dropped in limited editions on the same day as Film Music 1976 – 2020 hit on CD and double-LP. The track has a bizarre oneness and sense of self, and though the choral voices harken back to Eno’s earlier work, some of the computer glitch could be credited to an Eno descendant like Markus Popp. Simply put: it’s drop-dead gorgeous ambient music.

Eno has suggested to interviewers that he might have another film collection up his sleeve. and even beyond the already released stuff, there’s surely a treasure trove from which to borrow. Let’s hope, though, when he and the highers-up get ready to produce Film Music 2, they make it as singular an ambient experience as this first one. — Justin Vellucci, Spectrum Culture, Jan. 27, 2021

-30-