Beating The Dead Horse With Dw. Dunphy: A Profile

by Justin Vellucci

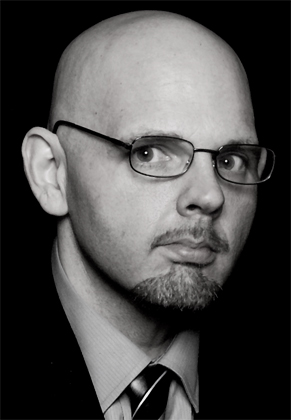

Dw. Dunphy’s face, a somber palette, is an exercise in disguise, spectacles covering hazel eyes that appear chiseled into their sockets, brown Van Dyke masking the angular chin beneath.

His music, however, an expansive catalog on which he has built for 15 years and that has few parallels in indie-rock circles, is as direct as a punch to the

gut and is imprinted deeply with passionate, direct messages – large, life-affirming statements – about the struggles of the common man, and about how one needs to grasp hold of precious moments in life because life is a trial and those moments, in modern times, have become far too rare.

His musical modus operandi, perhaps, is best summarized in “Crawling Toward Jerusalem,” a deceptively poppy song off Buckaroo, which I released on my label, Secret Decoder Records, in 2002.

“There are four walls / three of them blue / The fourth one is painted a different hue / Green is the color attributed to / The envious many and the privileged few,” he sings over a de-tuned guitar, strummed with thick reverb in something resembling a C or C minor. “Week ends the way it began / They’re working the jobs ‘til the jobs work them / There must be some other way to the promised land / than crawling toward Jerusalem.”

The song draws from America’s collective psyche –referencing cigarette addiction and the lottery, both arguably manifestations of that quest for the right to happiness handed down from generations before – but it’s that simple closing refrain that shakes the listener.

“There must be some other way to the promised land,” he wails, “than crawling toward Jerusalem, than crawling toward Jerusalem.”

Few artists with whom I have worked have influenced me as much as a musician, an independent artist or a writer as Dw. Dunphy. And I am not alone – for the better part of 20 years, Dw. has left fingerprints on an unassuming but sprawling nation, a loosely linked collective of co-conspirators and collaborators, a D.I.Y. network of Buzheads.

+ + +

Donald W. Dunphy, born Oct. 16, 1969 as the eldest son of an electrician shop owner and a home-maker, has lived most of his life in the same house, a white-walled ranch on a tree-shaded double lot that sits on a dead-end road off Route 35 in suburban Middletown, N.J.

Driving by that house, you never would know the magic that has been conjured up inside, a catalog worthy of Guided By Voices or Giant Sand.

But his remains the untold musician’s story.

Each of Dw.’s three siblings – he has an older sister and two younger brothers, all with phonetically similar names – have musical inclinations, have even formed bands, but the Dunphy family has not tasted fame. Their family branch of the Scots-Irish clan, though most of their blood is German- and Lithuanian-American, has never produced a Top 40 hit and, if Dw. is to be believed, never will. But Dw. grew up surrounded by people who expressed themselves artistically – as writers, as painters, as musicians. It just never added up.

all with phonetically similar names – have musical inclinations, have even formed bands, but the Dunphy family has not tasted fame. Their family branch of the Scots-Irish clan, though most of their blood is German- and Lithuanian-American, has never produced a Top 40 hit and, if Dw. is to be believed, never will. But Dw. grew up surrounded by people who expressed themselves artistically – as writers, as painters, as musicians. It just never added up.

Dw.’s music, even his earliest recordings, reflects upon this and is steeped in a deep-seeded sense of fatalism. He calls it an inheritance.

“How is it that the Dunphys could be so common a name in that part of the world and yet have so little to no recognition?” he asked me, sitting in the cluttered computer room where he does all of his recording these days. “The Dunphys seem to me to be like used matches, and what do most people think about used matches? Well, point of fact is that they don’t think about used matches at all. So, in tracing the genealogy, you find this long list of people who were highly ambitious down the line. They wanted to be business owners, artists, photographers, people of prominence. Yet things never really seemed to work out for them.”

Contrary to his tone, Dw. said his childhood “was, overall, stable and large portions of it were happy.” It also was filled with music. His father loved the crooners like Sinatra and Como, and his grandparents, who came from a more rural, farming background, listened to folk and country. His mother, though, loved pop and instructed Dw. in the fine art of appreciating the radio, which Dw. took to with fervor, developing early love for bands like The Cars.

“This was a great time to be interested in music because the genres weren’t all fragmented – you could go from Diana Ross to Queen to The Beatles to Kenny Rogers and Thin Lizzy and there was no over-riding segregation involved,” Dw. said. “It had a beat. it had hooks. it was pop music – period. “

His view of mainstream music today is far more complicated, something he has deconstructed and delineated not only as a musician working in popular forms, but as a writer and critic for such publications as PopDose and the ripely named ItstheCatsAss.com.

“[It] seems very much like DNA-splicing to grow perfect, little test-tube babies,” he said, sullenly. “A pop song can be broken down into the tiniest sub-genre, and the listener will be utterly devoted to that sub-genre and never once want to try anything new.”

In other words, in a pop landscape dominated by Britney wannabes and bands obsessed with fashionable throw-backs, what room is there for an independent singer-songwriter most influenced by Terry Taylor, Darren Richard, Paul Simon and Jimmy Webb?

+ + +

Dw. started his recording career by self-releasing a flurry of cassette-only recordings – shared under the moniker Dead Horse with a select circle of friends in the mid- to late-1990s – that hinted at the singer-songwriter genre then being popularized by acoustic, indie-folk musicians like Bill Callahan of Smog, Will Oldham of Palace and, later, Calexico and Iron & Wine.

But Dw.’s recordings always had grander ambitions. His second release, 1997’s idiopera was a song cycle in three parts that blended acoustic guitars with transient synth-washes. His Limb From Limb collection, which I released as a cassette the same year, featured explorations into both hard rock and traditional folk territory.

Or was that the beginning?

Dw. admits to experimenting with low-fi multi-tracking as a child – “I got two boom-boxes and a microphone … and I orchestrated a conversation with myself” – and he has come to regret his “first” record, Decapitator Tots, which, by name alone, should hint at its content.

“There were probably several cassettes recorded before Decapitator Tots and they don’t exist anymore,” Dw. said. “Even though I am my own worst critic, I can safely bet those tapes weren’t going to bring anyone any joy.”

It wasn’t until 2002, after he recorded but did not release a highly romantic record titled Separate Incidents, that Dw. seized the opportunity to start spreading his music beyond his circle of family and friends.

I released Buckaroo on Secret Decoder Records – Dw.’s sixth record but his first on CD – and the disc sold well, even generating reviews that compared his folksy approach to Bob Dylan. (Dw. was characteristically jaded about the compliments.)

The digital bug bit him hard. Dw. self-released through his Introverse Music four records in the next two years – The Look and Social Discomfort, the song-cycle Proud Sons of the Suburbs, the Crazy Talk EP and Gibberish – and among them is some of his finest work to date.

The digital bug bit him hard. Dw. self-released through his Introverse Music four records in the next two years – The Look and Social Discomfort, the song-cycle Proud Sons of the Suburbs, the Crazy Talk EP and Gibberish – and among them is some of his finest work to date.

“Digital was, in many respects, easier to make, easier to distribute and much less prone to [deterioration than] cassettes,” he said. “After all, from where I am, a cassette is just a copy of another cassette and that’s second or third generation or, considering how I work with multi-tracking, even fifth or sixth generation.”

It was around this time that Dw. solidified what could be described best as his “sound” – a meeting of the acoustic balladeering of his early work with lush, textured, synthetic soundscapes, but always with a chorus or a underlying harmony you could hum from memory.

+ + +

In late 2002, I invited Dw. to embark with me upon a bizarre musical experiment, a set of five songs tracking one person’s subconscious mind through an evening of sleep. Over the course of several months, we recorded together in every imaginable medium and with the most unconventional tactics. (One night, I smashed to bits a glass jar filled with pocket change –it made it onto the record – while Dw. played a series of glasses filled with water.)

The result – 2003’s Nightmare Variations – found Dw. and I mutating our own soundscapes, as well as contributions from Michael Catalano, a guitarist with the surf-rock band Hunchback, Michael Finnerty, the drummer from the post-punk band The Prisoner, and Inbal Kahanov Vellucci, a pianist and singer, into five epic post-prog-rock tracks. It was a mutant hybrid of experimental music that Punk Planet called a beautiful soundscape to get lost from this messy world into – high praise from high places.

“I don’t consider it so much my work as my compliment to a bigger thing, which was nice,” Dw. said. “It was like bringing a bag of random jigsaw puzzle pieces out, spreading them across a table and letting someone else arrange them in some way – and not being so tied to each piece that I felt wronged about their usage … With Nightmare Variations, I could bring these random bits and not feel overly paternal about them, and could get real pleasure from hearing how they would be used.”

The “broken record,” as its composers often referred to it, did have one exception from its edgy, ambient mode of attack – an untitled third track that was straight-from-the-heart folk-pop. Dw. sang the lead. The lyrics, which Dw. wrote for the fanzine Inner Limits in 1995, are worth quoting in their entirety, for they illustrate the way that Dw. imbues nostalgia with a pronounced undercurrent of melancholy and even regret.

“Grandpa was a sailor around 1963 / in some capacity for the Merchant Marines.

Scraping muck off the masthead, but he said / “The journey was like a dream.

When the sun bled through the salt-worn sails, / the occasional sightings of curious whales and dolphins

seemed more exciting than sorting cans / and bottles and discussions of bran and coffins.

So he talked about the mystical sea / and how it could be that the whole world was flat,

on a sheet of glass between heaven and hell . / Open the sail and see if you could dispute that.

And one of the metaphors he likes to repeat / from inside this amber-it room

is the tide being torn from the world / by the arms of the mistress moon

Grandpa never even boarded a ship. / Got a slip ‘round war-time of exemption.

It seemed the home-town tribulations and trials / could while the time but weren’t worth the mention.

The life of a sailor was so idealized, / who’d blame him for stylizing his history?

All he wanted was a noble tale, / something including dolphins, whales and mystery.

And somewhere between the Wheel of Fortune / and the Daily News at Noon

was the tide being torn from the world / by the arms of the mistress moon.

Somewhere, the tide was being torn from the world / by the arms of the mistress moon.”

+ + +

While putting together “jigsaw puzzle pieces” for Nightmare Variations,  Dw. was quietly –unknown to his collaborators on Nightmare Variations — at work on his follow-up to Buckaroo.

Dw. was quietly –unknown to his collaborators on Nightmare Variations — at work on his follow-up to Buckaroo.

The Look and Social Discomfort, which he self-released in 2003, became his finest record to date, a collection of tender and emotive indie-rock ballads and poppy ruminations that can be devastating to listen to from start to finish.

In one song, “Cannot Hear You,” he puts himself in his father’s shoes as he watches his wife, Dw.’s mother, dying of cancer in the spring of 2000. (Dw. has never played the song for his Dad.) The song unfurls with a softly strummed acoustic guitar – another signature Dw. de-tuned scale – and the pulse of a keyboard keeping time, and expands into a no-holds-barred ballad reflecting on the nature of love and loss. In another song, Dw. unravels a coda with a line that, depending on the listener, is either the zenith of optimism or pessimism: “If you follow the sun / you will never have to watch it set.” In a third, he reprises a song, previously released as an a cappella rendition in 1997, about a homeless woman seeking solace and stability in the only place she can find it: her dreams.

Though the volume and diversity of Dw’s work might call to mind Robert Pollard, it’s the sound of The Look and Social Discomfort that is often far more accessible. His Everyman lyrics here echo The Kinks’ Ray Davies, his love for catchy, verse-chorus-verse pop descends from early-period Elton John and late-period Simon & Garfunkel, and his method of engagement with listeners is classic D.I.Y. from the 1990s low-fi scene, another Guided By Voices parallel, perhaps.

Dw. distributed the record among friends, making no big deal of the whole thing, and moved on to the synthy song-cycle Proud Sons of the Suburbs. Gibberish, a collection of poppy instrumentals, was released to some fanfare in 2005 and remains a fan favorite due in part, Dw. says jokingly, that people don’t like his voice much.

Records followed in the coming years, each a memorable encapsulation of its time, a kind of State of the Union of indie-pop songwriting in its given month and year of publication. Dw. has released more records than there have been years since 1997 – you do the math. Each, as they say, is a treasure. Each, as they say, is a find.

+ + +

A few years ago, I devised a sort of biographical triptych on the D.I.Y.-minded musicians whose influence while I was coming into my own as an underground artist in New Jersey had left the biggest marks on me as a songwriter and, in some senses, as a listener and as a writer. Those three people were Dw. Dunphy, Michael Catalano and Peter C. Neusch.

All three were close friends. But my friendship and collaboration with Dw. Dunphy has, in many ways, defined my years as a musician and writer. His impact is profound.

Dw. always has been as influential as a mentor and as ephemeral as a shadow. He is constantly churning – writing poems and song lyrics and short stories, recording and releasing records, reviewing the work of others – but he is not heavy-handed about forcing people into his wake. In his day life, he’s an every-day white-collar worker, a writer and staffer for an association that publishes trade publications, among other activities. To know him, though, is not to know just another New Jersey desk jockey, another NPR listener, another underground rock critic.

To define him is to dive into his legacy as a songwriter.

And soaking in that legacy and the work that helped build it is easier than ever. All it takes is the flip of the CD or the click or Play on your iTunes.

And a little curiousity.