“The future’s eternally bankrupt but history provides”

Winter was hard on New York City. February 27, a Saturday, started before dawn for Erik Della Penna of Kill Henry Sugar, who rode the A train from his Central Park West apartment to 176th Street to walk across the George Washington Bridge, meet his sister for a ride and trek to Paramus, New Jersey, to take his weekly course in anatomy at Bergen Community College.

A bridge worker told him three-foot snowdrifts blocked the footpath on the bridge; once the man passed, Della Penna disregarded him, slipping through an unlocked gate. Then, halfway across the bridge, after pulling his knees up into his chest to plant his feet into the thigh-high mounds of snow, the sun still rising and the temperature lingering somewhere above freezing, he encountered the bridge workers. And they were less than pleased to see him.

“I was stopped by bridge staff, who held me ‘til two NYPD squad cars came,” Della Penna said. “The officers demanded I walk back the way I came, while they drove behind me – on I-95 – with lights spinning and megaphone blaring.”

Later that night, no worse for the wear, he entered Barbés, the intimate Park Slope, Brooklyn club that has become a second home for Kill Henry Sugar, soaking in the opening acts – the as-yet-unnamed jazz duo of Steve Ulrich and Itamar Ziegler, and blues guitarist Mamie Minch. Sometime around 10:15 p.m., Kill Henry Sugar – Della Penna and drummer Dean Sharenow – took the stage, a platform, really, officially launching this celebration to mark the release of its new record, Hot Messiah.

They entertained the packed, standing-room-only crowd for more than 90 minutes, playing 18 songs, all told, many of them from Hot Messiah. They covered Fats Waller and sang a cappella on “London Town.” On some songs, like “Bewildered” and “Against The Stars,” Sharenow stepped out from behind the drum kit to strum Della Penna’s Dobro guitar through Ulrich’s brown tweed amp as Della Penna, clad in a suit jacket, sang, his eyes occasionally closing to punctuate an emotion.

“I’m bewildered at you, bewildered at me/ the way of the world, including the sea/ Bewildered at creatures deep under the waves/ The way of our life and how it behaves,” Della Penna began, singing in his comfortable baritone in front of red curtains and under an antique tin ceiling, the setting more a parlor room than a rock club. “I’m bewildered how people manage to survive/ the way that they live, the way that they drive/ their cars on the road, like they’re invincible/ as if death is a magnet and closer they’re pulled.”

“It felt great,” Della Penna said afterwards. “We played and it could have happened anywhere, in any era. The fact that we had amplification was negligible. It could have happened anywhere. It could have happened around a fire in 1910, February 27. And that’s what I love about it, the primalness of it.”

“What was really nice about the show was I was instantly reminded, not only of how much satisfaction I get to play Kill Henry Sugar music … but, because of who we’d invited to play, I had such a fantastic time watching the other bands play,” Sharenow said. “It turned into an engaging evening of music, which I think doesn’t happen that much or happen that much in New York. It’s nice … for a lot of people to come out to a little club in Brooklyn to have a communal experience with music.”

Kill Henry Sugar helps form a New York City circle with Piñataland, Curtis Eller and Robin Aigner, indie musicians whose work is deeply informed by history and frequently feature historical events as the inspiration and content for their emotive song-vignettes. The Village Voice, writing about one of the bands, defined their sound, appropriately, perhaps, as “antique-garde.”

“This fascination with history, with the manipulation of history, the poetry, I guess, is alive,” Aigner said. ‘[There’s] just an incredibly deep appreciation for each other’s craft.”

What they’re doing is not, by any means, new.

There are contemporary, history-focused acts such as the Decemberists, of course, and legitimate Old Time acts focusing on Old Time themes. But, modern-era artists as diverse as Bob Dylan, Frank Black, Gordon Lightfoot and Iron Maiden have written history songs, said Doug Stone of Piñataland. And that says nothing of the long folk tradition of storytelling, or of storytellers working in verse dating back to Homer. This microcosm of New Yorkers, however, some full-time musicians, some part-time, wears its allegiance to history and all the magic and context it entails as a kind of badge of honor, as an identifying marker, a matter of allegiance.

These musicians frequently have shared live bills and performed together on stage, often at regular haunts such as Barbés, whose proprietor also books ethnic and World music. They have appeared on each other’s records and helped promote each other’s work. In interviews, they cite each other as influences.

“Oddly, my very first New York City show was with Piñataland at The Sidewalk Café,” Eller said. “Neither of us was writing the kind of tunes we’re writing now but, years later, we discovered that we’d dug our way down into the same mineshaft. It’s nice to have company down here.”

2010 is the unofficial year of the “antique-garde.” It started on January 28 with the release of Robin Aigner’s Bandito and continued in February with the release of Kill Henry Sugar’s highly anticipated Hot Messiah. Before the year ends, Piñataland and Curtis Eller will both issue new records, as will Piñataland’s David Wechsler under the project name Tyranny of Dave. If there is any time to take a closer look at the micro-scene, to place them and their work under the microscope, it is now.

Kill Henry Sugar

Dean Sharenow, one-half of the spare folk duo Kill Henry Sugar, is a third-generation New Yorker with Russian roots and, though he spent his high school years out in Arizona, he frequently trekked back to the East Coast to visit his sister, and perform and record in New York City as a teenager.

A drummer since the age of seven, Sharenow formally returned to the city, finding a place in the East Village, in 1988, at age 19, and threw himself into record engineering, a passion nurtured by his brother-in-law, Mike Rogers, who got him involved at D&D Recording on West 37th Street.

“D&D turned out a ton of rock, dance, and hip-hop, and was one of the centers of New York music in the 1980s,” said Sharenow, 40, a full-time musician, producer and sometimes-Web designer who lives on the Upper West Side, Manhattan. “I suppose it was partially through my work there that I discovered my real interests lay in the 1880s.”

Even then, a decade before Kill Henry Sugar formed and explored the delicate spaces between notes, Sharenow knew the value of silence. When he was producing hip-hop records, he had a trick he would use to win over artists in the studio. Right before a rousing chorus, he would drop out all the instrumental tracks, mute them all, and leave behind only the main vocals, naked and in your face, before kicking in the full mix right as the chorus punched in its climax. It worked every time.

“It’s so effective and beautiful to take everything out for a second,” said Sharenow, who sports a full, bushy beard and a scruffy haircut but manages to look clean-cut in photographs. “We keep the plane flying with as little fuel as possible.”

The singer-songwriter Erik Della Penna was born in the Bronx and raised on Long Island, returning to Manhattan at age 17 in 1983 and living in Washington Heights and in Brooklyn while attending the Mannes College of Music to study classical guitar and music theory. He would later live in Fort Green and Park Slope, Brooklyn, and the East and West villages.

Della Penna toyed with guitars on and off until he was thirteen, when he became very serious and dedicated to the instrument, he said. He has lived and worked as a full-time musician, supporting him and others, for 25 years.

Sharenow met Della Penna sometime around the early- to mid-‘90s, when both men were making the rounds in New York City’s thriving Irish ethnic music scene.

Fueled by a wave of Irish immigration to the city and its environs in the late ’80s and early ’90s, Sharenow and Della Penna would play pubs and venues like The Black Rose in the Bronx with musicians like fiddler Eileen Ivers and bassist Trevor Hutchinson. There was a high demand for authentic Irish music – this is “before all the River Dance bullshit,” Della Penna noted – and each musician typically could get paid as much as $100 a gig. And, there, among the proletariat, the newly arrived immigrants, they were awarded for good performances with tears, and learned and refined their craft.

“While I wasn’t Irish, I learned a lot about not being uptight and being a good musician … and having the music be a functional part of civic life,” said Della Penna, 44, a sometimes-scruffy man who wears his longish, salt-and-pepper hair either tied back or tucked behind his ears.

Around 1994 or 1995, the pair reconnected when they auditioned for spots as the live back-up band to pop-rock artist Joan Osborne. The tour was a success and the two, who shared rooms, felt a connection. One or both later would back Tiny Tim, Natalie Merchant and folk icon Joan Baez, among others. “Our interests were not just parallel,” Sharenow said. “It’s like finding your artistic partner.”

In 1999, Sharenow recorded a collection of Della Penna’s songs and they released it as the first Kill Henry Sugar LP. Though the group initially focused on a meatier, full, alt-rock sound, Sharenow and Della Penna said musicians who played with them tired of their eccentricities.

By late 2001, they officially solidified as a duo. Over the span of the next nine years, Kill Henry Sugar would release four riveting and sometimes-brilliant records, each featuring stripped-down and stirring songs that mixed the folk tradition of storytelling with early blues and rock n’ roll and a kind of Old World charm whose roots are difficult to map. The songs are distinctly New York songs, but New York is only sometimes mentioned. The duo likes to promote itself on its Web site by saying it lays bare the naked roots of Gotham. “Exquisite compositions, stunningly performed without a net,” Baez told the band.

“You really can hear an evolution but an evolution toward simplicity,” Sharenow said. “As time has gone on, we have found that we don’t need to wrap it up any more …. It doesn’t need the artifice of production. It doesn’t need multi-tracking. It doesn’t need overdubs.”

Sometimes, Kill Henry Sugar can sound like the inheritor of the Mississippi Delta Blues, a folk-blues band scattering its notes and hooks and frighteningly memorable melodies like unpolished gems at the floor near your feet. At other times, they sound like a post-rock act covering Johnny Cash; all the emotion and swagger is still there but the notes are stripped bare, each fragile and set in perfect place.

“[They perform] expressive rhythms and melodies that manage to sound both archival and brand new,” The New Yorker observed. “Kill Henry Sugar continues to show its strengths in inconspicuous ways, wedding intriguing lyrics to little textured grooves that have a habit of getting under your skin,” Mike Joyce wrote in The Washington Post.

Kill Henry Sugar splits its duties, with Della Penna writing the songs and Sharenow leading the record production. The inimitable Tom Waits once explained to Rip Rense of Performing Songwriter magazine how he and his wife, Kathleen Brennan, collaborate on making records; Sharenow sees similarities. “I’m the prospector, she’s the cook,” Waits told Rense. “She says, ‘You bring it home, I’ll cook it up.’ I think we sharpen each other like knives.”

“He’s the farmer,” Sharenow joked. “I’m the factory.”

The passing of a generation of New Yorkers – around the time Kill Henry Sugar formed – has left clear imprints on Della Penna’s songwriting. “When my grandparents died, I guess, I started seeing the New York I heard about going away.” he said. “There were young people coming in and I was like, ‘That’s not New York. That’s not New York.’”

“[When I arrived here] I hung out, played music, met people – the city was funky. I could name-drop for hours,” Della Penna added. “The city was alluring and seductive, a murky river to be swam in, to drink from. Now, New York City is a fitness center for out-of-town frat boys and sorority girls with trust funds.”

Della Penna, who had played his songs for grandparents who had emigrated to the U.S. from southern Italy, immortalized the sense of closeness to them and their passing in song.

“I’ll show you who you are, she said/ but just show me all your friends/ my grandmother, well, she told me this/ now she’s no longer here,” Della Penna laments over an acoustic guitar and a brushed share on “Company We Keep,” a hushed number from 2004’s “Love Beach.” “Some friendships made, they’re built to last/ while some are obsolete/ the building blocks that interlock/ well, I’m glad that you’re with me.”

Della Penna had read “Low Life,” Luc Sante’s brilliant book about the shadier side of life in New York City as the 19th century gave way to the 20th, a kind of document in the Joseph Mitchell or even Jacob Riis veins of the seediness, slums and inviting shadows lost in the official, modern-day histories of America’s largest city.

“That just lit the fire about the whole history of New York for me,” Della Penna said. “There’s definitely heavy source material to what I think about – not just songwriting but linking myself to the past, realizing that times were always tough.”

History looms large in the Kill Henry Sugar discography. The group has written songs about Italian fascist Benito Mussolini, Tammany Hall’s legendary Boss Tweed and, more recently, the eco-friendly wanderings of Johnny Appleseed. But the records are also packed with a sense for what the loss of history, no matter how obscure, means to society and its chroniclers. Della Penna dismisses himself as a chromosome away from a Renaissance storyteller, merely spinning yarns for an eager audience. But he also compares himself, maybe more fittingly, to Cervantes’s Don Quixote, someone somehow noble yet also delusional about the trappings of a lost age, a bygone era.

“Art usually works that way,” Della Penna said. “They always write the history that is out of grasp, the fetishizing of history just out of reach.”

In February, the pair amicably separated from Surprise Truck Records, a Hollywood-based indie label, and self-released “Hot Messiah,” their sixth record and one of their finest to date. The collection was recorded – mostly – on a houseboat docked on the Hudson River in Garrison, N.Y. and opens with “Yankee Talk,” a rousing number whose rhythms and repetitions gradually unfurl. The song, a good example of self-reflexive, post-modern storytelling, places Sharenow and Della Penn among the “volk” whose traditional forms of storytelling they seem so fond of co-opting.

“Well, we descended from some European trash/ though we would not assimilate into the children of the corn/ The custom agent’s only taking cash /‘cause he knows we’ll all be dying in the class that we were born,” Della Penna sings, his voice captivating and expressive. “Had we been wronged, had we been broke/ by helping hands, had we been choked/ It’s that way for Dean and me, Yankee talk with many shades of meaning.”

(The song goes on to detail a confrontation between soldiers and mobs, Della Penna and Sharenow caught in the midst of it, and notes, very matter-of-factly, “you can hire half the working class to kill the other half.”)

The record features more than a handful of gems and, throughout the proceedings, the band sounds more comfortable experimenting with the blues, especially of the Mississippi Delta variety, than they have on previous recordings. “Hot Messiah” is also darker, musically and lyrically, than its predecessor, 2007’s “Swing Back And Down,” and, at times, more direct in confronting the listener with what the loss of history means.

“I’ve developed, in Kill Henry Sugar, despite the other stuff I’ve done,” Sharenow told me. “Erik and I found our sound and we always strive in our band to play as little as possible. If it’s possible to not play, we don’t play. With two guys, if one guy is not playing, you are making a huge statement.”

“The idea of playing less and less and less has really been a huge factor. I think all good art comes down to that,” he continued. “The stuff that really moves me is where you see what they could have done but didn’t …. I think what isn’t said is so much more important than what is, especially in music.”

Piñataland

About five years ago, the core members of Piñataland – David Wechsler, Doug Stone and Bill Gerstel – were invited to play a live set for a group of young prisoners, most of them aged 18 to 21, on Riker’s Island. An appearance on NPR brought the group to the attention of a prison teacher.

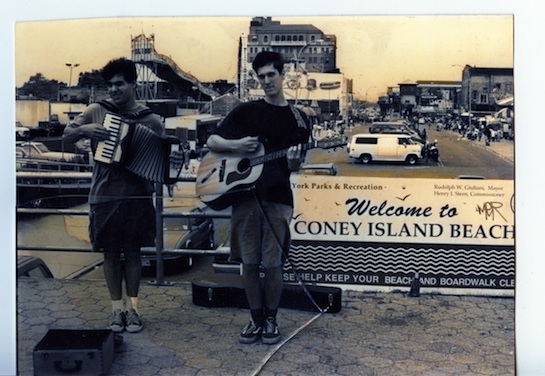

The group was used to playing their songs in unusual spaces. Over the years, they’ve performed in the Atlantic Avenue subway tunnel (complete with miner’s flashlights), an abandoned church in Braddock, Pa., the Edison Museum, a Brooklyn mausoleum, and the Coney Island boardwalk. They even performed a marching song to celebrate the New York Times’ transition to color printing on that newspaper’s loading docks.

But the audience on Riker’s island was different.

The trio, after checking their gear through metal detectors, played “Ota Benga’s Name,” a song about a Congolese Pygmy displayed at the turn of the century with the monkeys at the Bronx Zoo, and “The General Slocum Disaster,” a piece about a boat that caught fire in the East River, not far from Riker’s Island.

After the set, a worried prison administrator confronted the band, demanding answers about their intentions and asking what he was supposed to say in his official report about their visit. “What is it you guys do?” the administrator pressed, frustrated.

“It was very odd – I said, ‘I don’t know,’” said Doug Stone, 39, a screenwriter who lives in Prospect Heights, Brooklyn. “Someone was demanding that we justify our existence. And I didn’t have an answer for them.”

“I don’t think we were too helpful. We didn’t really fit in,” said Wechsler, who turns 39 April 7. “It’s really hard to describe our music and describe what it is we do.”

Like Kill Henry Sugar and the rest of this circle of musicians, Piñataland has always confounded those who seek to categorize them. Formed in late 1994 by songwriters Wechsler and Stone, who met as students at Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachussetts, the group’s first incarnation was more of a comedy routine, a manic country-polka act with some Tex-Mex overtones whose work was heavily influenced by the Old World jazz-pop of Little Jack Melody and His Young Turks. The melodies were frantic and the first EP, a self-titled affair, skittered and scattered all over the place. They made an early appearance on Comedy Central.

By 2003, however – and after another, more developed EP, Songs From Konjin Kok – the group really had found its wings, when it self-released what continues to be a hallmark of the historical-vignette genre, the brilliant Songs From The Forgotten Future Vol. 1. It begins, appropriately, with a bold thesis statement: “The future’s eternally bankrupt but history provides.”

“Goodbye to the Gramercy Ball/ It’s gone now and no one survived/ All of the best things that money can pay/ Have passed on their problems to those who have stayed/ All the mistakes that we paid for on credit/ And prayed for have finally been made,” Wechsler sings over a barely audible acoustic guitar before a pedal steel steps in.

“So buy your time from someone you trust/ And I’ll buy mine from a cold blooded schemer/ Who lies as he cheats me and claims that it’s just,” he adds, before the song expands into an orchestra, led by a soaring guitar. “All of the pockets where money collides/ Are emptying out right in front of your eyes/ The future’s eternally bankrupt but history provides.”

In just 10 songs and 50 minutes, Piñataland takes the listener through a musical fun-house of obscure history, singing beautifully arranged songs about the 1939 World’s Fair; the exploited Pygmy Ota Benga; the destruction of much of East Tremont to construct the Cross-Bronx Expressway; and Mathias Rust, a German teenager who flew a single-engine plane through the Iron Curtain and straight into Red Square in 1987. The band closes the proceedings with the epic “Latvian Bride,” where weeping strings form a wall of sound that can be emotionally overwhelming. The record, a combination of alt-country-flavored Americana, orchestral pop and Island-era Tom Waits, even a touch of They Might Be Giants, was one of the finest releases of the year and drew raves from countless underground magazines. This music was ambitious, even cinematic in scope.

“The album’s tone is reflective, as if the band unearthed a 20th century time capsule hundreds of years from now and decided the best way to understand this forgotten culture was to write ballads about it – timeless ballads full of explosive dynamics, strange instrumentation and ethereal harmonies,” Steve Labate wrote in Paste in late 2003.

“When the Decemberists came out, I was like, ‘This should have been us,’” said Gerstel, 55, a full-time musician and lanky, sometimes-manic drummer with dyed-red hair who came to New York City in 1980 and now lives in the East Village. “All of that could have been us.”

Shortly after Vol. 1 was released, Wechsler left Brooklyn to pursue real estate, musical theatre and a master’s degree out in Chicago, living in Irving Park. The band continued writing and performing, aided by the Internet and interstate commutes. It was around this time that Robin Aigner, a folk singer-songwriter in her own right, joined the band. She had met Piñataland after the band played a set at Freddy’s in Park Slope, Brooklyn, and eventually asked if she could provide backing vocals.

“I think my first show with them was at Joe’s Pub,” Aigner said. “They are such an interesting juxtaposition of the contemporary and the nostalgic.”

“Since Robin joined the band and our performances became more focused on our male-female harmonies, my songwriting has changed for the better,” said Stone, who has clear blue eyes that project curiosity and wears his brown hair short. “Now, when I write, I think about how her personality is going to inform the song …. It’s a bit like how Black Francis and Kim Deal worked in The Pixies. Kim didn’t sing lead on a lot of tunes, but her vocal presence was vital to make the music more expansive, to give it more of a human personality. Imagine ‘Doolittle’ without her and you get ‘Trompe le Monde’ – good tunes, but a serious lack of heart. And that’s what she brings to Piñataland, and it’s a big deal for us.”

In 2004, The Village Voice named Piñataland the city’s “best dark old-weird-history orchestrette.” They applauded them for Vol. 1 and the recording and online release of a John Quincy Adams political anthem, complete with the name John Kerry woven throughout.

With the new group and a host of songs in place, studio work began in late 2007 at Wombat Studios in Park Slope, Brooklyn on Songs For The Forgotten Future Vol. 2, with producer JD Foster – who has recorded alt-country troubadour Richard Buckner, southwestern desert-rockers Calexico and the breathtaking guitarist Mark Ribot – at the helm. Foster engineered some songs, aided with arrangements and played bass on about 60 percent of the record. Sometimes, he said he was merely a band cheerleader.

“Their take on history is more defining than their musical style,” said Foster, 56, of downtown Manhattan, who met the group through Gerstel. “It’s really interesting that the band is kind of interested in shining the flashlight in the little cobwebby corners and writing songs about it. It’s a reason to exist.”

Foster enjoyed seeing the different ways in which Wechsler and Stone worked as songwriters and composers. “I’d say Doug comes from a purer pop songwriting place than I do,” said Wechsler, the soft-spoken member of the group, whose brown hair sometimes falls over his eyes and his round face. “I’m a fan of written arrangements, complicated interactions, close harmonies and the like, while Doug usually just wants to clear that all out of the way and just let the song come through.”

“He cleans up my songs and makes them less cluttered and more listenable,” he continued. “I take his songs and add compositional depth and unexpected musical hooks that wouldn’t be there otherwise. It was great having JD [Foster] in the studio with us ’cause he’d sort through the different approaches and pick the best way for any particular moment before it got to Doug and I just butting heads against each other.”

Vol. 2 ended up being far more commercially and aesthetically accessible than its predecessor – a slice of orchestral Americana, some songs poppy and yet still heavy on the pedal steel. “Centralia” – a song about a Columbia County, Pennsylvania town that was abandoned, sometimes forcibly, after a mine fire started (and didn’t stop) burning underground in 1962 – even shook off the Old World cobwebs, sounding stunningly modern.

Wechsler thinks the group’s interest in history is a New York City phenomenon. “New York is one of those places that’s always sort of eating its tail and reinventing itself,” said Wechsler, citing Ouroboros. “So it’s a great place to put a new spin on history – or an old spin, depending on how you look at it.”

Stone draws his views on history from childhood experience. Stone’s father, Leland, worked as a colonel and hospital administrator for the U.S. Army and, like children in military families, Stone called many places home over the years. He lived in Germany early in elementary school and, stateside, he settled in South Carolina, Maryland and Texas. When living in Forest Glen, Maryland, he found National Park Seminary, a politician’s retreat that was reinvented as a girl’s school before Walter Reed Army Hospital bought it in 1942 as a home for convalescing soldiers. In addition to various Victorian styles, the buildings on site included a Dutch windmill, a Swiss chalet, a Japanese pagoda, an Italian villa, and an English castle.

“Everything was falling apart (and) it was a place that was designed in the 1800s to look historic,” Stone recalled for me. “Living in this environment, you have a real sense of history being present and all jumbled up.”

“I came away with a feeling how, when you can spot a certain kind of historical record … it can kind of fill your imagination,” he continued. “It makes your life better.”

Piñataland is now at work on its third full-length record, a 10-song collection tentatively dubbed Boy Scouts of Democracy, a title borrowed from a dismissive comment Stone said Adolf Hitler made about American GIs. The record, which boasts its share of history songs but is not “Songs For The Forgotten Future Vol. 3,” should hit streets before the close of 2010.

“It’s a little more of a stripped-down record but that could change, depending on what we do on it,” said Stone, who said the songs maximize the interplay between his and Aigner’s vocal harmonies. “[It’s] more straight-forward. Hopefully, you’ll get a little more sense of the performers …. It’s still an unformed thing.”

Wechsler also has a new record in the works. His second release as Tyranny of Dave, a 12-track outing, is due to be released online April 7. It is titled The Decline of America, Part 1: The Bush Years.

“It’s not actually a political album [but] most the songs are personal, reflective for that period,” Wechsler said. “There [are] songs about the economy. There’s a song about New Orleans. There’s a song about the World Trade Center coming down. I’m just trying to branch out, do other stuff.”

Robin Aigner

She has opened for Emmylou Harris in Nashville, played festivals in Europe and Canada with the Crooked Jades, loves the work of Gillian Welch and has flirted with both New York’s Old Time and anti-folk scenes. But, Robin Aigner is a musician who, like her peers, is difficult to peg down to simple musical categories. She is a square peg in a musical genre-game filled with round holes. She is a beautiful anomaly.

Her new record, Bandito, which was released in late January, only adds ammunition to the spirited argument that “folk singer” is too reductive or simplistic a term to describe what Aigner musically concocts in the studio and on stage.

The record begins with an acoustic guitar, almost jazzy and seductive, slowly shuffling just below the surface of things, low in the mix, as Caroline Shaw’s violin weeps and Joshua Camp runs his fingers over the keys of a piano, dosing out spare but perfectly timed notes.

Then, Aigner sings and her voice instantly becomes a magnet for the listener’s ears. You are drawn into her orbit. She is at the center of the world.

“I’ve been to the Campbell Apartment/ at the invitation of F.D.R./ I’m the only one who knows where he goes when he parks his car,” she coos, her voice soaked in sensuality and dropping more than a hint of double entendre. “You can’t believe the papers, periodicals you read/ I’m a lady first and foremost, doer of good deeds.”

Then, Shaw’s violin returns, weeping over Camp’s lonely piano. The effect is devastating.

The song is “Pearl Polly Adler,” an engaging homage to a New York City Madame and Russian immigrant whose houses of ill repute were supported by the likes of mobster Dutch Schultz and served the gangsters and politicians of her day. And it’s the kind of brilliant moment that can be found throughout “Bandito,” Aigner’s second solo record and her first in almost eight years. It is a record that, like those of Tin Hat Trio, sits at the eclectic intersection of jazz, American folk and Eastern European gypsy music. It is an expressive and expansive disc.

But, how did she arrive here? After a series of live sets at New York City clubs like The Living Room, Sidewalk Cafe, and Pete’s Candy Store, Aigner, a sparkly eyed, curly-haired chanteuse who stands much taller than her small, five-foot-three frame suggests, formally introduced herself to musical audiences in 2002 with Volksinger, a 15-track CD of acoustic ballads and odes that Aigner hoped would project a “lonesome prairie” sound but sometimes, maybe even more appropriately, calls to mind the heart-wrenching cowgirl blues of Edith Frost’s Calling Over Time. Then came Royal Pine, her duo with multi-instrumentalist Brook Martinez, and two excellent records steeped in alt-country and Americana – 2004’s Chantytown and 2007’s Huasteca, which had an ultra-limited run and was mostly shared among friends and confidantes.

Aigner toured widely and even traveled to Romania in 2003 with the New York City act Luminescent Orchestrii, a forerunner in that city’s Balkan music scene, to study Eastern European music in a small Transylvanian village (When the locals found out Americans were in town, a night of Old Time American music was planned and staged at the village’s town hall. Aigner played ukulele and sang. Someone translated the performance into Hungarian for members of the crowd.) Her musical palette was diversifying. But something very basic about Aigner’s songwriting is central to what makes her work so appealing, said one musician versed in Old Time music.

“She really caught my ear with her voice – she has a natural, fluid, beautiful delivery,” said Parrish Ellis, 35, of Asheville, North Carolina, a guitarist for The Wiyos who met Aigner in New York City while he was playing in an Old Time string band about seven or eight years ago. “She’s a tremendous songwriter but her voice is under-rated.”

Ellis traces Aigner’s songwriting back to the sensibilities of Tin Pan Alley, even though the inheritors of that tradition might be today’s pop and Top 40 superstars. “She’s got that craft to it,” Ellis said. “All the elements are there and they fit together – the pacing, the phrasing of the melody, the lyrics being clever and still intellectually stimulating, just interesting chord progressions that you want to do over and over again.”

But, on the incredible Bandito, Aigner is more of a driving or central force than a solitary one. Aside from one song – the closing “Great Molasses Disaster,” which is so fragile, ethereal and quiet it feels like eavesdropping on a whispered conversation between lovers – Aigner surrounds, even engulfs, herself with sound, whether it’s a violin, Sharenow’s beautifully understated percussion, an upright bass or the throbbing pulse of the Rhodes organ.

“I think Song For The Forgotten Future Vol. 1 was a huge influence on Bandito,” said Aigner, 41, a freelance copy-editor and writer who has called Brooklyn home for 14 years and now lives in a co-op in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. “I loved the layering of different instrumentation from that album, and especially the violin. I used a lot of violin on Bandito and did more layering on that album than I ever had on other recordings.”

“Plus, I work a lot with Dave Wechsler on his solo projects, doing harmonies, et cetera,” she added. “So I think that experience, being around such an incredible songwriter and composer, has been invaluable.”

Aigner’s connection to history – and her ability to recreate historical moments in song – is something wholly her own, said Matt Singer, a Brooklyn musician with whom she has collaborated.

“When she’s talked about actual historical events, my experience is that she does a great job of creating a personal story that helps a person feel like what the event might feel like,” said Singer, 32, of Park Slope, Brooklyn, a social worker and musician who first saw Aigner perform around 2001 at the familiar Sidewalk Café. He is releasing a live record in two parts this year.

“I see her as someone from a different generation and a different time and place than most songwriters I know,” Singer said. “Most of the songwriters that I know pretty much fall into a modern pop-folk acoustic genre and Robin just seems to be very comfortable in a mood and a style of presentation that you could have seen at any time.”

“She has songs that could be comfortable being listened to anywhere in America in the [past] two centuries,” he said. (Singer and Aigner collaborated on a cover of The Strokes’ “Heart In A Cage,” with Singer on acoustic guitar and vocals and Aigner on melodica, about five years ago. It still can be viewed on YouTube.)

Aigner has been no stranger to the indie press. In 2006, the Web site Treble voted Aigner one of the most overlooked female performers in the country. Folk Radio UK described her new record as a meeting between The Decemberists, Tom Waits, Beirut and Leonard Cohen— high praise from any critic, indeed.

Music – and songwriting – came to Aigner late. “I tried to play the flute in about third grade, gave it up when I couldn’t hold a note for the required amount of time,” Aigner told me. “Also played the recorder but gave that all up by about fifth grade. Tried to learn guitar in high school, gave that up for obscure English imports, then picked it up again as an adult.”

Aigner is not extensively trained. After proudly walking away from a developing career in the New York City publishing world in the 1990s, she studied acting for three years at a West Village studio, waiting tables at a Mexican restaurant to pay her rent, then just $795 a month. After giving up on acting, she briefly studied guitar and took voice lessons. But she was quick to write her own material.

One night, while waiting tables at an expensive Italian restaurant in Brooklyn, she was inspired to write a song. So, between delivering food and taking orders, she’d scribble down lyrics on spare pieces of paper. The result was “Stone Cold Mamacita,” something of a minor hit in some Brooklyn circles.”

“I’m a stone cold mamacita with an ex-pat hippie papa/ We gotta lot of terra cotta. We’re a long way from home,” it begins. “We live on wit and vino rojo in our orange El Camino/ Our perro’s name is Pedro and he’s a long way from home.”

It is the only song in Aigner’s catalog to be recorded twice – once on “Volksinger” and once on Royal Pine’s “Huasteca,” complete with backing vocals and an accenting guitar line played with a bottleneck slide.

Even today, her songwriting can be spontaneous, not labored. “I usually get an idea in my head – like I’ve been trying to write a song from the perspective of Joseph Smith’s wife, when he came to her with a revised version of the ‘Book of Mormon,’ with a new revelation that encourages polygamy,” Aigner said. “So I will get an idea and try to write a song around it. But, sometimes, I just pick up an instrument and start playing something and a line will come to me. Then I decide after that line what the song will be about.”

“That happened recently with a song now called ‘Shoegazer,’” she continued. “I picked up the guitar, started playing something and this came out: ‘Is it a crime, to be 59, and be told you look cute? When you know it’s just the color of your shoe. Or the clicking of your high, high-heeled boots.’ It seemed so absurd to me that that’s what would come out of my mouth. So, I decided that the song was about a shoe fetishist and went from there.”

Aigner admits elements of her own life slip into songs. One of the most effecting songs on “Bandito” details the ambiguity of a romantic relationship. She said it is drawn from personal experiences.

“You only see me in the night-time/ when the sun goes down/ Are you around?/ See you around,” she sings, almost bitingly, over a carefully strummed acoustic guitar and the buzz of the Rhodes organ. “Did you know my eyes aren’t blue?/ They change in the afternoon/ Did you know I have a crooked bottom tooth/ some have called cute?”

“I could make a meal for a king/ sing a tune about any damned thing,” she later wails, pleading with the nameless lover. “You would know all of these things/ if you were around.”

New York City and her native Brooklyn also play prominent roles in Aigner’s creative life. “I’m inspired by my surroundings and, since I live in Brooklyn, and, despite the fact that I write about historical events that take place elsewhere, little pieces of Brooklyn inevitably end up in the songs, little details,” said Aigner, who, before moving to Sunset Park, lived in Park Slope, Brooklyn. “But, also, there is such a wealth of musical diversity in this city that you can’t help but stylistically be influenced by it.”

Curtis Eller

Gee Jon became the first man executed in an American gas chamber when he was killed on February 8, 1924 in Nevada. Several states soon thereafter abandoned the electric chair and followed the new practice, including North Carolina. According to a North Carolina Department of Corrections Web site, the state first used the gas chamber on January 24, 1936 to execute Allen Foster, a man sentenced to death for murder in Hoke County.

Curtis Eller heard a slightly more colorful version of the same story.

“The way I heard that story is that in the late 30’s in North Carolina, they were instituting a new capital punishment device that we all know now as the gas chamber,” said Eller, 40, a full-time musician from Astoria, Queens. “In an attempt to learn if the procedure was painful or inhumane, they placed a microphone in the chamber with the condemned man, waiting to hear what he would say. Not surprisingly, the guy in the chamber was black and his last words turned out to be, ‘Save me, Joe Louis, save me!’”

More stories were written at one time about Louis, an African-American prizefighter from Eller’s hometown of Detroit, than were written about Jesus Christ, Eller said. So, he added one more to the canon.

“Here’s hoping things get better/ after I’m gone away/ If I was there with you I would drink myself blind/ But these hard times could be here all day,” Eller sings over his signature banjo on “Save Me, Joe Louis,” which closes 2008’s Wirewalkers and Assassins with a chorus that borders on a gospel rite. “And Mr. Roosevelt in the White House/ can deliver no comfort down here/ And I know that it’s only a paper moon/ but it’s the last hope to fight back this fear.”

Eller – whose wild, curly hair and conspicuous, brushy moustache jump out in photographs, where he’s often shot in full suits or in shirts with suspenders – was born and raised around suburban Detroit and took part in musical theatre in Michigan and North Carolina before moving with his then-girlfriend, the poster artist Jamie B. Woolcott, to New York City in 1995. (The pair met at a vintage musical instrument shop, where they both worked, in Lansing, Michigan, and have been together since 1991.)

Eller had visited New York City previously but the move was transformational. Within a year or two of his arrival, Eller dedicated himself entirely to the banjo and started playing live shows at venues such as The Sidewalk Café, a staple of New York City’s anti-folk scene. He shared his first bill with Piñataland, with whom he would later collaborate on Songs For The Forgotten Future Vol. 2.

“Growing up in Detroit, your idea of the city was that it was a big, terrifying, empty place that you should avoid,” Eller said. “Visiting New York in the 80’s kind of opened my eyes.”

In 1999, Eller self-released an EP of his banjo-driven songs. Soon after, a full-length record, titled 1890, and another EP, Banjo Music for Funerals, followed. Two more recent full-length records – 2004’s Taking Up Serpents Again and Wirewalkers and Assassins – drew critical acclaim for their engaging combination of boxcar folk, bluegrass-tinged balladry and rousing, full-band toe-tappers like “Sugar In My Coffin.”

“They’re putting water in the whiskey just to keep the boys in line/ You ain’t a-busting up my place like you did last time/ The drinks are getting weaker with every round they serve/ The way they keep us sober, man, it’s getting on my nerves,” he sings in “Sugar In My Coffin” over lively banjo, thumping bass, spare drums and what sounds like an accordion. “So, when I’m dead and gone/ I want some sugar in my coffin/ Well, I said, ‘If I’ve got to go/ I want sugar in my coffin.’”

Eller’s music is the oldest-sounding, in the Old Time sense, of this circle of New York City musicians, perhaps due to the instrumentation he chooses to populate his songs. Banjo is prominent, taking center stage along with Eller’s voice, as is the upright bass. Some reviewers cited the records as experiments in Old Time music.

“I think if I played guitar, people would just call me a folksinger,” Eller said. But Eller’s live shows – which seemed to draw as much from the well of punk rock tradition as that of folk – are truly something to be experienced, those who have experienced them say.

“Most performers will get up on the stage and they’ll stand and sing and play their songs at the microphone and they’ll stay there the whole set,” said Joseph “Joebass” DeJarnette, 34, an Eller collaborator, producer and former upright bassist for The Wiyos, a band with Old Time credentials, who moved in December from Prospect Heights, Brooklyn, to rural southwestern Virginia. “I’ve never seen Curtis stay on the microphone, on the stage for more than three songs.”

Eller walks on tables, tells the audience stories and teaches them to yodel, sprints around the stage and acts in a manner one would expect from someone who proudly identifies himself as “New York’s angriest, yodeling, acrobatic banjo player.”

“Curtis Eller gives a master class in how to command the attention of a room,” Kid Pensioner wrote in the U.K.-based Venue magazine. “Go and see Curtis Eller. One day, you’ll be able to say you saw him in a tiny venue before he was huge.”

“Basically, what it does is that it reduces the barrier between audience and performer,” said DeJarnette, who has performed with Eller both as part of a live band and in the studio and might be producing his new record. “So, the audience is really involved in what he’s doing.”

Andy Whitehouse has been active in promoting Eller’s shows from his home overseas.

“I had a venue called The Circle. I had a punky blues band from Sheffield [England] booked and the agent rang me and said, ‘Andy, would it be okay if we brought New York’s angriest yodeling banjo player as support?’ It took about 3 milliseconds to say, ‘Yes,’” said Whitehouse, 46, who works with young adults with autism and Asperger’s syndrome and lives in Sheffield, England. “So I looked Curtis up online and found this footage of an awkward guy who reminded me of Tom Waits and Randy Newman and had this bizarre, nervy stage presence. I was hooked!”

“I think a lot of English artists shy away from the notion of being ‘entertainers,’” Whitehouse added. “Curtis is the most breathlessly entertaining performer I can ever remember seeing. He is assessing every audience all the time and responding to what is happening. It’s fascinating to watch him.”

Eller got an early education in performance and the value of giving paying patrons their money’s worth. His father, Robert, a gym teacher by trade, ran a small-time circus called Hiller Old Time Circus and the younger Eller gained entertainment experience as both a juggler and acrobat. Robert “Bob” Eller also played bluegrass banjo and rockabilly guitar for a Baptist church in their native Michigan and he taught his son the ways and means of the bluegrass banjo when Curtis was just 13, formative years for the teenager.

“Banjo players were like the punk-rockers of their time,” Eller said. “It’s a highly physical, harmonically simple music that is designed to get people sweaty.”

When it came to writing his own material, Eller started around age 18 and was inspired by 1920s-era banjo players like Dock Boggs, Old Time string bands, and the 1960s Old Time revivalists The Holy Modal Rounders, one of the first acts Eller said used the term “psychedelic” in song. “[The Holy Modal Rounders] are giants for me,” Eller said. “They sort of established the playbook on how to be modern and stand in one spot and work backwards – great music.”

Eller stresses, despite the banjo and the anachronistic airs, he is no member of the Old Time crowd. “I sing about old things but the songs are not constructed like actual old songs. A lot of people aren’t familiar with Old Time music,” Eller said. “[My music] is somewhere between folk and rock n’ roll music.”

It’s more about music that actually moves and rolls itself around, making you move with the sound.

“It’s splitting the difference between 1928 and 1961,” Eller explained. “The writing is much more closely related to people like Randy Newman or The Kinks – modern songs about old things.”

In another song off “Taking Up Serpents Again,” Eller laments the current, deteriorating state of the film and entertainment industries by calling for the return, the resurrection, even, of silent film marvel Buster Keaton.

“Well, since they started in with the talkies/ you can’t get a moment’s peace,” Eller sings over a lonely banjo. “But they’re talking just to hear/ their own voices, well at least/ that’s what it seems like/ ‘cause there’s nothing that I’ve heard that bears repeatin’/ Won’t you come back to the movies, Buster Keaton?”

“It sums up the sense of loss of a world that perhaps never was but is yearned for,” Whitehouse said.

The era of the silent film and of vaudeville, and the artistry both embodied, loom large in Eller’s work. History and the capturing of history are ever-present. But, Eller strongly disputes accounts in the underground press that say he writes about obscure historical figures.

“I concern myself with the most prominent historical and political characters out there,” Eller said. “Abraham Lincoln, Elvis Presley and Richard Nixon seem to show up frequently. I think if you understand Elvis, Lincoln and Nixon you know everything you need to know about America.”

“I’ve also written about John Wilkes Booth, Amelia Earhart, Buster Keaton, Jack Ruby and Boss Tweed,” he added. “None of these can really be considered obscure. If anybody around here is obscure, it’s me.”

As a full-time musician, Eller spends a lot of time on the road, touring both nationally and internationally. When he’s in the studio, which he will be later this year, he likes to work quickly, capturing the energy and vitality of his performances and those of his backing band. Sessions take hours and days, not weeks and months.

Eller has been doing this full-time for nearly a decade. He gave up his last day job, a gig answering phones for an architect down in Greenwich Village, shortly after day-to-day life in New York City was turned upside-down by the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.

“If there’s a chance that everybody in the world is going to die, I don’t want to die with a phone in my hand,” Eller remembered thinking. “I’d rather die with a banjo in my hand than a phone.”

Eller, who plays a regular gig at Banjo Jim’s in the East Village, said he’ll be releasing a new record, maybe two, before the end of the year but he’s also quick to talk about his daughter, Daisy, who turns three March 30.

“Daisy has been strumming away on the [ukulele], banjo and mandolin for a while now,” said the proud father, whose voice changes, if only slightly, when he talks about his daughter. “She often ‘writes’ tunes about what’s going on in her life. It’s really very cute.”

“I suspect I’ll be opening for her one of these days!” – American Songwriter, March 30, 2010

-30-